All throughout history, people have gone to extraordinary lengths to avoid infections.

In the Middle Ages, it was common to douse oneself in “four thieves vinegar” – a concoction of herbs brewed in cider vinegar – before leaving the house, as a way of staving off the plague. Legend has it that a group of grave robbers invented it to keep them safe. Eventually they were arrested, but the authorities agreed to let them go in exchange for their secret recipe.

In 16th-Century Sardinia, things were a bit more sophisticated. The doctor Quinto Tiberio Angelerio devised an ingenious method of social distancing, in which “any person going out from home must carry a cane six spans long [the distance measured by a human hand], and as long as the cane is, one must not approach other people”. In his spookily prescient manual on the sanitary measures to be taken during an outbreak in the city of Alghero, he also recommended only one person per household venture out to do the shopping, and urged his readers to be careful when shaking hands.

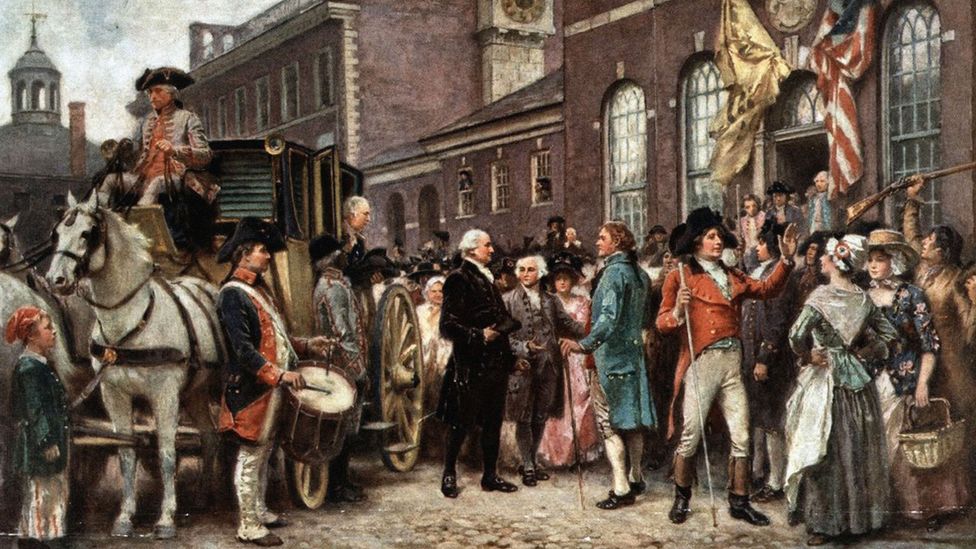

In 1793, the US government simply evacuated entire sections of Philadelphia – the then-capital – to protect residents from a yellow fever outbreak. An estimated 20,000 people left the city over the course of a month, which amounted to half its population at the time.

Other precautions adopted by our ancestors include toad-vomit lozenges, developed by none other than the celebrated physicist Sir Isaac Newton during the Black Death, and an alarmingly recent dental practise: in the 1940s, women would routinely have all their teeth removed, just in case they ever went septic. The preventative was so popular, it was often paid for as part of a wedding gift, or for their 18th birthday. (Happy birthday, you now need dentures!)

You might also like:

- The strange ingredients in vaccines

- Why the elderly are harder to vaccinate

- How Covid-19 is changing the flu

Even centuries before we knew about microorganisms, antibodies or vaccination, people had a pretty good idea that being infected was something to avoid at all costs.

In 2020, cracks began to appear in this previously universal thinking. Early in the Covid-19 pandemic, it was reported some people were considering the – deeply risky and highly dubious – strategy of catching Covid-19 on purpose, as a way to fast-track their route back to normal life. The terms “immunity passport” and “herd immunity” became part of the mainstream lexicon, and low antibody counts in the population were framed as a “blow” rather than a success.

Now a group of scientists has signed a controversial statement – the Great Barrington Declaration – which criticises the imposition of lockdowns, and instead calls for what they call “focused protection”. Drawn up by a group of two epidemiologists and a health economist, the claims the most compassionate approach to the pandemic would be to “allow those who are at minimal risk of death to live their lives normally to build up immunity to the virus through natural infection, while better protecting those who are at highest risk”. It has attracted thousands of signatures since it was unveiled, but many of their claims have been questioned by others in the scientific community.

Philadelphia was a bustling city in 19793 - but 20,000 of its inhabitants had to be evacuated due to a yellow fever outbreak (Credit: J L G Ferris/Getty Images)

In some places, however, infections have even become an implicit part of the national strategy.

In Sweden, the Folkhälsomyndigheten (FHM), or public health agency, has taken what is arguably one of the most relaxed approaches in Europe. The country is currently entering its first lockdown, but for most of the last year, it has remained a rare bastion of normality. The state epidemiologist Anders Tegnell has actively discouraged the public from wearing masks, and while much of the rest of Europe has been housebound, the Nordic nation has been mingling freely in bars, gyms, shops and restaurants. Back in July, the FHM claimed that the rate of immunity in the capital, Stockholm, could be as high as 40%, and was already pushing back the virus.

This may all soon be behind us. It looks increasingly like there are at least two viable vaccines on the horizon, and the German immunologist behind one of them – the Pfizer-BioNTech version – recently predicted that the pandemic will be over by next winter.

But for now, the pandemic continues. Covid-19 cases are rising rapidly in the US, France, Belgium, Germany, Italy, Russia, the UK, India, Mexico, Sweden, and Greece. Russia has turned an ice rink into a hospital, the Indonesian capital, Jakarta, is running out of graves, and Spain has declared a state of national emergency. The situation in America has been described as the “last big surge”.

As we’re still faced with the uneasy dichotomy of lockdowns verses mass infection, here’s a rundown of the reasons experts are so enamoured with the first option – and why you really don’t want to catch any kind of pathogen on purpose.

Vaccines can be more protective

In February 2009, a brand new flu virus emerged from a pig farm in eastern Mexico.

To begin with, infected pigs began to cough or ”bark”, producing a harsh, reverberating noise like the honking of geese. Over the coming days, victims could be found suffering from sticky noses and red eyes, breathing with their mouths wide open and feeling generally reluctant to get up. Some developed a temperature and experienced sneezing fits, while others had no symptoms whatsoever.

One day, it’s thought to have hopped from a sickly pig to a human in a nearby mountain village – possibly a six-year old boy, possibly a baby girl. From there, it quickly swept around the globe. By May, at least 18 countries had been affected. As of July, it had been found in 168, and there were cases on every continent. This was a pandemic.

But while the world’s attention was focused on tracking the spread of this mysterious virus, something extraordinary was happening – people infected by it were acquiring a kind of universal protection to other types of the flu.

Left to their own devices, our immune systems tend to hone in the “head” of a virus particle, making antibodies that can identify this part. But this is a mistake. The flu is a famously slippery beast, and the head evolves rapidly – meaning that this generally only provides protection against the specific strain that you have been exposed to. All other flu viruses remain unrecognisable. This is why we can catch the flu again and again, and why it’s necessary for the more vulnerable to have flu vaccines annually.

This time it was different. It just so happens that, when exposed to swine flu, sometimes our immune systems are able to side-step their usual blunder – and focus their attention on the much-more-stable “stalk” of the virus instead, which is shared between lots of different types.

“When we analysed the antibody responses that some of the infected people had made,” says Ahmed Rafi, the Director of the Emory Vaccine Center, Georgia, “we found that that many of the antibodies that were generated were very broadly cross reactive.” This meant they weren’t just effective against the H1N1 strain they were made for – but to many other flu viruses as well.

The number of deaths from Covid-19 has show intentional infection is a risky option (Credit: Adek Berry/Getty Images)

The result was radical. The ability to recognise the stalk is thought to have been so potently useful, some scientists think it explains another event that coincided with the pandemic. Every other kind of influenza A that had existed up until that point in humans – the only type that causes pandemics, as well as most cases of seasonal flu – abruptly disappeared. It looks as if, by training the body to recognise many other flu viruses, H1N1 made its closest relatives extinct.

But if this leaves you thinking that catching swine flu sounds like a good deal, you might want to reconsider. Like the strain behind the 1918 pandemic, the virus has the unusual habit of killing young people. It’s also been linked to the development of autoimmune conditions, including type 1 diabetes and narcolepsy. And though the fatality rate has turned out to be low overall, this took years to establish.

Instead, insights from the swine flu pandemic are being channelled into developing what could become the first universal flu vaccines. “That paper was very influential in the strategy that is now being used by many research groups,” says Rafi. Until his discovery, no one knew if they were even possible. But in 2018, nearly a decade after the swine flu pandemic, such a vaccine finally made it to Phase III clinical trials – large-scale tests in humans that help to assess the safety and effectiveness of medical interventions.

This is the first big advantage of modern vaccines. “Not all natural infections cause long-lasting immunity,” says Beate Kampmann, who is a professor of infection and immunity at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine and director of its vaccine centre. “This is a big deal in the context of Covid-19, because the coronaviruses generally don't. So, if you think about the vaccine, if you want long-lasting immunity, you have to do better than nature.”

To achieve this, scientists can draw on more than a century of knowledge and expertise in making vaccines. Some contain specific proteins painstakingly selected for their ability to generate enduring immunity – like those found in swine flu. They often include added ingredients – from shark liver oil to aluminium – that contribute to their effectiveness. (Read more about the strange ingredients added to vaccines.)

Then there’s the way they’re taken – vaccines can be injected into muscle or below the skin, blasted at the skin in a jet of fluid, introduced via microneedles, ingested on a sugar cube, or inhaled.

“The technology that you use for vaccination can swing the profile of the immune response a little bit,” says Kampmann. She gives the example of the BCG. The tuberculosis vaccine is injected into the skin, rather than the muscle – and this helps it to interact more closely with a person’s T cells, whose main job is to attack infected cells, rather than produce antibodies. It just so happens this is the optimal strategy for this pathogen.

Vaccines is that they provide the opportunity to generate immunity in large numbers of people all at once (Credit: Getty Images)

“So, the vaccine reaches a different sort of distribution. It's almost like there’s a street map of the immune system, and if you take a vaccine one way rather than another you’re taking the M1 rather than the M25,” says Kampmann.

There are already a number of vaccines which can be more protective than natural infections, including the zoster, Hib, HPV, and tetanus vaccines.

People who receive the live zoster virus in vaccine form are around 20 times less likely to develop shingles in adulthood than people who catch chickenpox – which is caused by the same virus – in childhood. The Hib vaccine – which protects against the Haemophilus Influenzae type b bacterium, is particularly effective in children, in whom natural infections lead to a negligible immune response. People who have been infected with tetanus do not have any natural immunity and can be infected again; almost 100% of vaccinated individuals are protected.

And while natural infections with HPV generate a minimal immune response – some people don’t produce any detectable antibodies – the vaccine can protect people for up to nine years. This ingenious technology is made from the protein that normally coats the virus, which self-assembles into particles that resemble it – known as virus-like particles – as it’s being manufactured. The protein is more concentrated in the vaccine than the virus, which is thought to help increase the potency of the immune response.

In other cases, vaccination would clearly be preferable to natural infection because once you’re infected, the pathogen never goes away. Famous examples include HSV-2, which causes genital herpes, and HIV. There aren’t yet any licensed vaccines that can prevent either, but a candidate for the former has already shown promising results in animal studies, while a potential option for the latter has passed the first safety test in humans.

All this means that becoming infected with Covid-19 may not have the same payoff as receiving the vaccine.

In October, researchers from Imperial College London estimated that the number of people in the UK with antibodies to the virus is likely to have fallen between June and October. The findings made international headlines and caused widespread alarm, with many concerned that this suggests it’s possible to be reinfected with Covid-19 regularly – and that this would inevitably mean vaccines wouldn’t provide lasting protection either.

However, as a number of experts pointed out, this is not necessarily the case. For example, the study didn’t look at T-cell immunity – a kind of lasting protection thought to play an important role in the severity of Covid-19 infections. But crucially, vaccines are very different to natural infections.

Herd immunity is a kind of disease resistance that occurs within a population (Credit: Getty Images)

It’s not yet clear how the immunity generated by infection with Covid-19 compares to that produced by the vaccines currently in clinical trials – including those made by Pfizer/BioNTech and Moderna, which have released preliminary results demonstrating above 90% and 94.5% effectiveness respectively. However, early results from trials in animals suggest that some vaccine candidates lead to higher antibody levels than are found in the blood of recovered patents. This suggests they might be more protective than natural infections.

Another crucial advantage of vaccines is that they provide the opportunity to generate immunity in large numbers of people all at once.

Herd immunity usually happens via vaccines

Early in the Covid-19 pandemic, Italy was one of the hardest-hit countries on the planet. And within it, Bergamo – a northern province encompassing 1.1 million people and covering 2,755 sq km (1,064 sq miles) – was the epicentre of the outbreak.

Though Bergamo is usually renowned for its alpine vistas, vineyards and medieval history, suddenly this was a place where ambulance sirens wailed all through the day and night, doctors were faced with heart-breaking moral dilemmas about who to prioritise for intensive care beds, and many older patients reportedly died alone.

In one tragic case, a 74-year-old priest was gifted a ventilator by his adoring congregation. It might have saved his life – but instead he donated it to someone younger, and died shortly afterwards.

As of September, scientists have estimated that around 38.5% of people in Bergamo had antibodies against Covid-19, suggesting that around 420,000 people in the province have been infected. There are only a handful of other places where such a high proportion of people are thought to have contracted the virus, including the Brazilian city of Manaus, where roughly 66% of people have antibodies.

In both Bergamo and Manaus, the number of Covid-19 cases has tailed off dramatically, possibly as a result of herd immunity curtailing the virus’ spread. But there are several reasons that this is ordinarily achieved with vaccines – and why it’s unusual to discuss the concept in the context of natural infections.

Herd immunity is a kind of disease resistance that occurs within a population, as a result of the build-up of immunity in individuals. It doesn’t make viruses disappear completely, but limits their spread as long as they are contagious – it doesn’t work for infections that are caught in other ways. If few people are susceptible to a certain pathogen, there won’t be much of it in circulation.

When exposed to swine flu, sometimes our immune systems are able to side-step their usual blunder (Credit: Mario Vazquez/Getty Images)

Contrary to popular belief, there is no reliable threshold at which herd immunity can be reached, such as the commonly-cited 66% of people for Covid-19. Instead, the point at which it materialises depends the reproduction (R) number, which represents the number of people that the average person infects. Where the R number is high, the number of people that need to be immune before herd immunity kicks in is high also. This is the case for measles, where each person infects around 15 others and around 90-95% of the population needs to be protected at all times.

In reality, this means that there is unlikely to be a single, reliable threshold at which herd immunity is reached for Covid-19. The R number varies around the world, and depends on our behaviour and the level of immunity in the population. It’s also not usually evenly distributed across a population – for example, it might be higher in cities and certain demographics.

As a result, estimates for the number of people that need to be immune to the virus to end the pandemic have ranged from 85% in Bahrain to 5.66% in Kuwait, according to an article published by the journal Nature.

This is one reason relying on the population building up herd immunity naturally is usually not recommended. Due to its dynamic nature, it can be hard to spot and quick to slip away. It can also be totally impractical; if 85% of people need to be infected to achieve it, you’re reaching the point where it’s not protecting many people who haven’t already had the virus – and shielding the most vulnerable members of society might be impractical.

Secondly, it’s possible that people who have been infected with Covid-19 once will still be able to catch it and spread it again, even if they don’t develop symptoms the second time – as is the case for some seasonal cold viruses. If this kind of immunity doesn’t halt onward transmission, herd immunity may never materialise.

Thirdly, herd immunity can come at a steep price. In Bergamo alone, there have been 3,100 deaths, while in Manaus around one in every 500-800 people has been killed by the disease. Catching any pathogen is a gamble – especially one that’s new to humankind. Sometimes, the cost of an infection doesn’t show up for months or years afterwards; HPV can take years to lead to cervical cancer, while HSV-1 has recently been linked to Alzheimer’s disease.

A wide range of longer-term health problems are now believed to be caused by Covid-19 in those who have been infected – something that has now become known as “long-Covid”.

No one knows how enduring long Covid will be. The syndrome of fatigue, breathlessness, brain fog and joint pain, among other things, occurs in one in 20 people who have recovered from Covid-19. There are already signs that the consequences of the pandemic might be with us for years to come.

One medieval cure for plagues was to suck on toad-flavoured lozenges (Credit: Mathias Delle/Getty Images)

Preliminary data from one study suggests that almost 70% of people with long Covid have impairments in one or more organs four months after they first developed symptoms of infection. This includes damage to the heart, lungs, liver, kidneys, spleen and pancreas.

A follow-up study of patients who were hospitalised with another coronavirus infection, Sars, 15 years previously recently found that, while their lungs tended to recover substantially within the first year after infection, there was very little change after that.

Meanwhile a large-scale analysis of the evidence found that the survivors of Mers and Sars often found it hard to exercise and this did not improve much beyond six months afterwards. There was also a “considerable prevalence” of lingering psychological disorders. The authors speculated this may have implications for the long-term prospects of those who have been infected with Covid-19.

If this is true, it may well be preferable to minimise the number of infections. Looking at humanity’s long history of desperate, even nauseating strategies for avoiding infection, you might say it’s the least we can do.

Staying home, keeping your distance, wearing a mask, and washing your hands should be easy – certainly better than toad vomit-flavoured lozenges or the prospect of tooth pulling.

--

Join one million Future fans by liking us on Facebook, or follow us on Twitter or Instagram.

If you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter, called “The Essential List”. A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Culture, Worklife, and Travel, delivered to your inbox every Friday.

"want" - Google News

November 20, 2020 at 03:00PM

https://ift.tt/35ULOlh

Why you really don't want to catch Covid-19 - BBC News

"want" - Google News

https://ift.tt/31yeVa2

https://ift.tt/2YsHiXz

Bagikan Berita Ini

0 Response to "Why you really don't want to catch Covid-19 - BBC News"

Post a Comment