And the Dude will abide cancer.

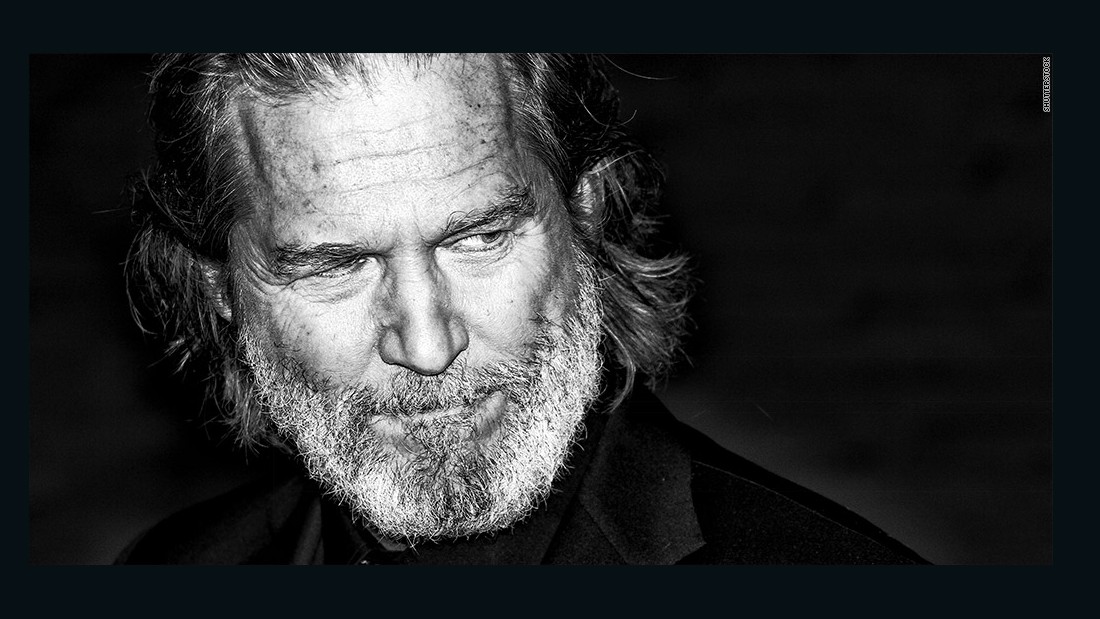

At least that's my most sincere hope for Jeff Bridges, the Oscar-winning actor who played the character "The Dude" in that most excellent 1998 film, "The Big Lebowski."

Bridges announced on Monday night via Twitter that he had been diagnosed with lymphoma -- a blood cancer that starts in the lymphatic system.

Most people could more easily find Vladivostok, Russia, on a map than find their own lymphatic system, but let me try to help.

Have you ever gone to a doctor with a potential infection and had them feel around the sides of your neck? Well, they were likely feeling for your lymph nodes there. You have these small oval-shaped glands all over your body -- including in your armpits, your groin and behind your knees. Your 600 lymph nodes are where your body filters out bad stuff -- like toxins and infections.

I know all this because I was diagnosed with lymphoma in July 2013.

Early that year, I had found an odd bump on my thigh. A few weeks later, that little bump had grown to the size of a grape. Over the next couple of months, it grew to the size of a ping pong ball and then further to the proportions of a small egg. That's when I insisted on surgery to get it out of me, despite an MRI that had come back benign, and grumbling from my then-primary care physician that I was being alarmist. Malignant or benign, grumble or endorsement, I didn't want this alien growing inside me anymore.

Waking up from surgery, groggy from the anesthesia, I saw in front of me something you never want to see in these situations -- a grim-faced doctor. He told my wife and me that he had bad news: I had one of two ailments, either cat-scratch fever or lymphoma.

Before that moment, the only "cat-scratch fever" I knew was a 1977 song by Ted Nugent. My amazing wife, Jenn, quickly Googled it and learned that the sickness by the same name is tough to get. As the CDC says, it's transmitted when "an infected cat licks a person's open wound, or bites or scratches a person hard enough to break the surface of the skin." That seemed highly unlikely since a) we have no cats, b) I'm not really a "cat person" and c) I certainly hadn't had THAT kind of contact with a cat.

So, unfortunately, that left lymphoma. At 41 years old, I had to face the dreaded "c-word" -- cancer.

I was petrified. Despite the amazing support of my family and friends, I felt absolutely alone. I had barely even heard of lymphoma before my diagnosis. I surely didn't know anyone with lymphoma. Most devastatingly, I was worried that I had just received a death sentence.

But, as I laid out in a prior CNN.com opinion piece written when then-Goldman Sachs chief Lloyd Blankfein was diagnosed with the disease, I quickly learned it was not a death sentence and I was not alone.

In the tweet announcing his diagnosis, Mr. Bridges wrote, "New S**T has come to light." It's a classic line uttered by The Dude in "The Big Lebowski." Bridges was, of course, referring to his cancer diagnosis itself in his tweet, but you could also say a lot of new s**t has come to light in the world of lymphoma and this s**t is really exciting.

Twenty-five years ago, the standard of care for many lymphomas was a pretty brutal regimen of chemotherapy. For those uninitiated to cancer, it's rather stunning to learn that another way of thinking about chemotherapy is simply this: You are essentially putting poison in your body. Now let me be clear: Chemotherapy has saved countless millions of lives. But while it can be extremely efficient at killing the cancer cells in your body, it will also certainly cause some collateral damage. That's why you can lose your hair, for instance, or have bouts of nausea.

When I went through treatment seven years ago, I had a relatively tolerable chemo regimen -- just a few infusions in manageable doses, then daily sessions of radiation targeted at the area where my tumor had been removed. I did, in fact, lose my hair from the chemo (and most of my sense of taste, too -- everything tasted "gray," even my favorite food: pizza).

Included in my chemo cocktail was a drug called rituximab, which isn't chemotherapy at all but one of the first-ever immune therapies -- a way to use the body's own immune system to fight illness. Here's how this one works: It attaches itself to a protein found on the bad cells (and some of the good ones, too) and tells the body's immune system to come destroy those cells. The foot soldiers of the immune system do what they are told and zap the cells. If all goes well, the good ones grow back, the bad ones don't, and the patient goes on to live a long life.

Rituximab was introduced in 1997 and the death rate for the major subtype of lymphoma has been declining ever since. And it's not just rituximab, according to Meghan Gutierrez. She's the CEO of the Lymphoma Research Foundation (LRF), a non-profit dedicated to funding research to find a cure while also educating and supporting patients who are facing down the disease. In the 25 years LRF has been in existence, more than 100 new therapies (and new uses for old ones) have been approved for lymphoma and related cancers. That's almost unheard of for one disease, Gutierrez told me. I should note: I learned a lot from the foundation when I was sick and I now sit on its board of directors.

Thanks to the work of nonprofits like LRF, governmental agencies like the National Cancer Institute, and research scientists and clinicians around the world, the future looks brighter. My own oncologist, Memorial Sloan Kettering's Dr. Connie Batlevi, told me that "cool" developments abound.

Batlevi points to CAR T-Cell therapy which goes even further to super-charge the body's own immune system to fight lymphoma.

There's also a push, Batlevi says, to use genetics to guide treatment. If you remember back to your high school biology, our cells are constantly dividing. When those cells divide, a genetic error can make them divide in an uncontrolled manner. That's how cancer forms. If doctors know what kind of genetic error caused a patient's cancer, they can pinpoint a very specific treatment plan based on that mutation.

Lymphoma vaccines are another weapon scientists are currently testing in clinical trials. When we think of vaccines these days, our minds go immediately to the push for a vaccine to inoculate us against Covid-19. But, as the American Cancer Society explains, the lymphoma vaccine would not prevent the disease but to treat somebody who already has it: "to create an immune reaction against lymphoma cells."

"Do I have one of the good lymphomas or one of the bad ones?" That's the question Dr. Batlevi says patients ask her all the time. Her response: "None of them are great but all of them are potentially manageable and curable."

I can tell you from personal experience that it's true. And let me be very clear: this is a deadly disease. It has killed friends and acquaintances of mine, and it kills 20,000 people every year. But as science continues to rapidly innovate, prospects will only get better and life will only get easier for those of us diagnosed with this and other cancers.

Bridges shared few details of his diagnosis in his tweets but betrayed a welcome sense of optimism: "The prognosis is good...[I] will keep you posted on my recovery."

Sounds good, Mr. Bridges. We're all rooting for you and wishing you an easy course of treatment and many peaceful years of life on the other side of it!

"want" - Google News

October 24, 2020 at 06:47AM

https://ift.tt/34n7bKV

What I want to tell Jeff Bridges about lymphoma - CNN

"want" - Google News

https://ift.tt/31yeVa2

https://ift.tt/2YsHiXz

Bagikan Berita Ini

0 Response to "What I want to tell Jeff Bridges about lymphoma - CNN"

Post a Comment